Apache Airflow for the confused

explained using airplanes 🛫

At NYC City Planning, I was looking for a tool to automate a data pipeline process we had built. When I discovered Airflow, I thought it might solve my problem, but I wasn’t sure. I couldn’t find a clear explanation of what it was that didn’t include technical language. This is my attempt at a simplified primer of Airflow.

Airflow can sound more complicated than it is.

Fundamentally, Airflow is an orchestrator of a sequence of tasks. It was designed primarily for tasks that move, analyze, and transform data. Most tutorials will assume you will be using it for this purpose. But it could also schedule a tweet to your mom on her birthday and or call random pay phones. Airflow doesn’t care.

Airflow does this by giving you a language and templates to define sequences of tasks. These tasks can be any number of things a computer can do–running a script, querying a database, sending an email, waiting for a file to appear on a server. Airflow manages when these sequences should run, what order to run the tasks in each sequence, and what to do if a task fails. It also manages the resources necessary to run these tasks, scheduling tasks as computing resources are made available.

Airflow’s primary responsibilities are:

- Task scheduling and triggering, including error handling and logging what happened.

- Managing the resources necessary to run these tasks. Resources can range from one server to entire clusters. When a task is due to be run, Airflow decides when and how to run it depending on the resources available.

- Providing a structured way for defining a sequence of tasks (they are just objects in Python).

- Setting and storing variables and external connection configurations to be referenced by tasks. This helps manage the databases and services tasks will need to talk to.

A Metaphor

It’s helpful to think of Airflow like an air traffic controller.

An air traffic controller manages a finite amount of resources (airspace and runways), orchestrating sequences of tasks (flight paths, takeoffs, landings, and taxiing) that depend on whether other tasks have completed successfully.

Airflow, like an air traffic controller, keeps detailed logs of each of these sequences: what command was given, how that command was executed, and how long it took. And if, tragically, there is an error, it knows if it needs to try again, or to notify someone else for help.

We’ll come back to this metaphor later.

Airflow Terms

Airflow uses several terms that can be unclear or jargony to new users but are actually straightforward concepts. The words can be strange at first, but we’ll flesh them out.

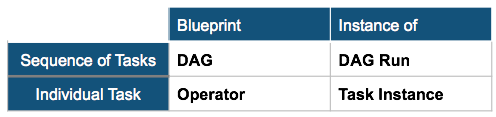

The four key terms to understand are: a DAG, an Operator, a DAG Run, and a Task Instance.

Let’s continue with our air traffic metaphor.

Air France flight 11 between New York and Paris is a flight route defined by Air France. It is, in essence, a sequence of tasks that gets an airplane from JFK to CDG. Air France defines how often this sequence should be run. In the case of AF11, it’s run daily.

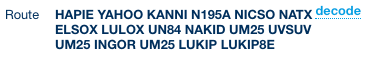

A flight route is made up of many different tasks: taxiing to a runway, taking off, raising the landing gear, navigating to waypoints, etc. Some of these tasks can be run in parallel, some in sequence, and some depend on others before happening.

An Airflow DAG is like a flight route. It defines a sequence of operations and how often they should be run.

In Airflow, a DAG is made up of Operators. Operators define the individual tasks that need to be done. They can trigger bash commands, run SQL on a database, transfer data between systems, listen for changes on a server, or even send an email or Slack message. Airflow comes packaged with several built-in Operators and even more are available through open source libraries.

To recap: a DAG is made up of Operators, and together they form the blueprint of a work flow. The DAG defines the sequence and schedule of operations, the Operators define discrete tasks that need to take place within this sequence.

So what happens when a DAG is executed? It becomes a DAG Run.

A DAG Run is what Airflow calls an executed instance of a DAG. Airflow triggers this execution based on the schedule defined in the DAG (hourly, daily, weekly, etc.). Once triggered, Airflow orchestrates the execution of the Operators in the correct order, assigning available computing power to any outstanding tasks that need to be completed.

Airflow calls an executed Operator a Task Instance. (This is an example of where Airflow’s naming conventions could be much clearer). A Task Instance is the most granular concept in Airflow. It represents an attempted operation at a certain time, with certain parameters.

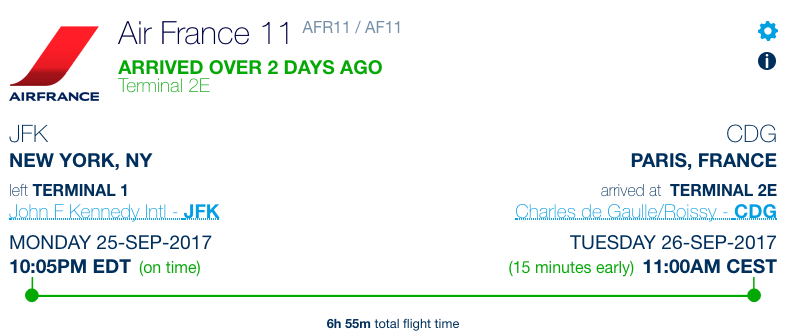

Returning to our air traffic controller metaphor, Air France Flight 11 on Monday, September 25, 2017 took off at 10:05pm EDT and landed in Paris the next day. This flight followed a sequence of operations defined by the airline to get a plane from JFK to CDG. AF11 on Sept 25 is the DAG Run to the daily AF11 flight route’s DAG.

Recap

The four core concepts in Airflow are:

An Airflow DAG is a defined sequence of operations. An Airflow DAG is a Python script that defines what should be run, how often, in what order (in sequence or in parallel), and what to do if an error might occur. (If you’re interest in the maths behind DAGs, they’ve been showing up a lot these days).

Operators are the blueprints for individual operations. A DAG is made up of one or many operators. These define the individual tasks that make up a DAG. Airflow defines three types of Operators–actions, transfers, and sensors–and provides many built-in operator classes to interact with common databases and other systems.

A DAG Run, is an executed run of tasks defined by a DAG. A DAG Run is logged, including when the run began, exited, and if any errors occurred along the way.

A Task Instance is an executed Operator. It’s log contains the exact command that was given to a server, at what time, and the detailed output of what occurred.

Why Airflow

Airflow’s primary strength is that it is language and technology agnostic.

It doesn’t care what you trigger. This means you can have scripts written in whatever languages make the most sense for your workflow. All that matters is that these scripts are granular (they only do one thing) and that they return a success or failure.

Another strength is Airflow’s configuration as code.

Because Airflow’s task definitions–DAGs and Operators–are just Python, it gives tremendous flexibility in how to define a workflow. For example, it allows a DAG to dynamically add new Operators based on files in a directory. This makes it possible to define a DAG that dynamically creates new tasks when additional scripts are added to a folder, or for several DAGs to import a collection of Operators defined in another Python file.

Airflow is a fast-moving project. No doubt some of these concepts may change or be renamed in the coming years. Confusing terminology aside, its flexibility and active open-source community have proven to be very valuable. Within a few weeks, I was able to convert an existing data generation workflow to use Airflow.